Using the Special Collections for Library Outreach

Barbara Opar and Lucy Campbell, column editors

Column by Cindy Frank

The University of Maryland’s Architecture Library, housed in the School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, is lucky enough to have its own Special Collections room. However, for the past several years, it has been a hidden gem. The books were rarely requested and current faculty seemed unaware of the collections. The enthusiasm of a new graduate student employee caused me to re-visit the collection with an eye towards getting more of the School community in there.

The Special Collections consist of approximately 1,500 items, including eighteenth and nineteenth century oversize monographs, plates from Le Castel Beranger Oeuvre de Hector Guimard, small brochures on seventeenth century building techniques, and Josef Albers’ Interaction of Color study set.

The Special Collections room is climate controlled and many items are fragile, so we began by discussing logistics with the Maryland Libraries conservation team. The Head of Preservation was enthusiastic and brought one of her managers to visit, who happened to know the collection quite well. He was able to suggest certain monographs for display and volunteered to discuss the collection during the open house, as well as protect certain volumes from over-eager hands. We wanted visitors to be able to actually touch the books if they wished, so we chose several books that were sturdy enough to be handled, and displayed them separately from more fragile items.

The open house took place the Tuesday after Thanksgiving, from 4:30 PM to 6 PM. The library closes to the public at 4 PM, and we intentionally limited the audience to the School and Library communities. An architecture student designed invitations, which were printed and placed in all faculty mailboxes. The event was advertised on the School’s Facebook page, and via printed posters in studio. Email invitations were sent to Libraries staff, as well as the School community.

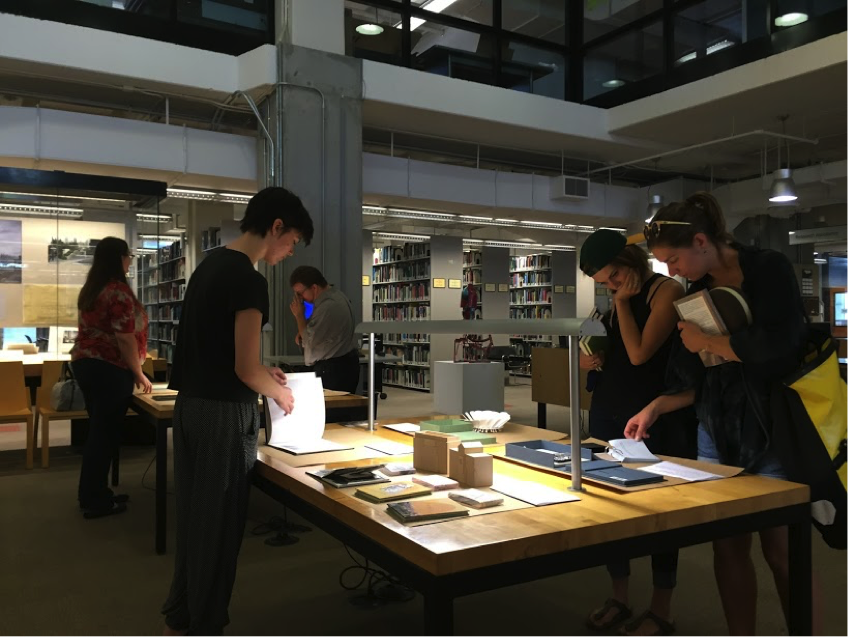

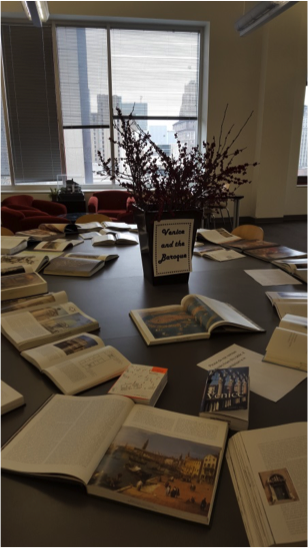

The conservation staff and my students pulled out certain monographs, including DesGodetz’ Rendering of Antiquities that were displayed on top of the flat files within the Special Collections room. Other items of interest were brought out to the two large tables in the reading room of the library. We used foam wedges to support larger monographs, and acrylic cradles for smaller books. One table had books and plates that could be touched; the other table had Charles Garnier’s Le Nouvel Opera de Paris open to the section through the theatre. The Head of Conservation stood next to that monograph and turned pages when asked.

I am delighted to report that my campus library colleagues stopped by, and so did many faculty and students of the School. One of the architecture historians asked me for some scans of the plates of Paris shop fronts, for her Modern Architecture seminar. The architecture program Director asked if we would open the Special Collections room for the Spring open house. Another professor suggested we do this again based on a particular theme, for example: Ancient Rome, European Churches, or Colonial America. There is enough material to feature several unique holdings from the Collections. The majority of students who attended were in the architecture program, and they were quite excited to see oversize books with plans, sections and elevation drawings spread out.

The good will and enthusiasm has carried over the winter break into this semester. On the first day of class, one of the studio professors brought his students up to look at our Letarouilly 3-volume set. The open house reminded the faculty of the resource that they have down the hall as well; I am interested to see if there is an uptick in the number of items requested from the Special Collections during this semester. I highly recommend this type of event to get people into the library. Although it took some planning and coordination, the interest it generated was well worth the effort.

Study Architecture

Study Architecture  ProPEL

ProPEL

Understanding the idea of the “total work of art” can be an important lesson for students and, recently, more attention has been drawn to it. Gesamtkunstwerk has once again become a subject of numerous discussions, proving that this idea is still relevant. The exhibition, “Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk” in Kunsthaus Zurich (1983) and in Vienna (1984), a recreation and performance of Skriabin’s “Prometheus” at Yale University (2010), and the latest collection of essays, “The Death and Life of the Total Work of Art,” presented at the Bauhaus Colloquium in 2013, highlight the historic meaning of the term, and apply it to more recent events and works. Technological advancements provide the tools that allow for the creation of immersive artistic experiences, which remove “the borderline between object and observer, stage and audience, art work and spectator,”

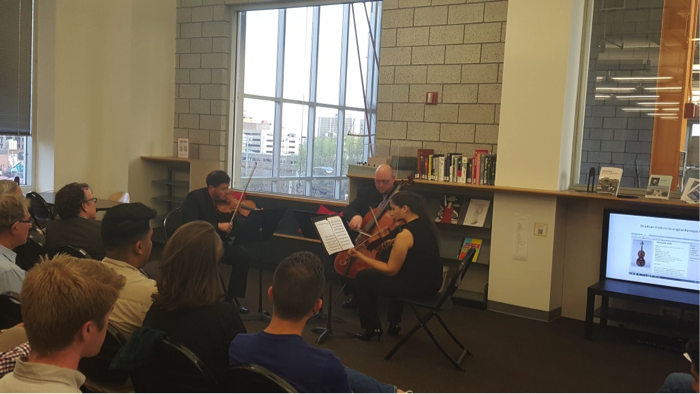

Understanding the idea of the “total work of art” can be an important lesson for students and, recently, more attention has been drawn to it. Gesamtkunstwerk has once again become a subject of numerous discussions, proving that this idea is still relevant. The exhibition, “Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk” in Kunsthaus Zurich (1983) and in Vienna (1984), a recreation and performance of Skriabin’s “Prometheus” at Yale University (2010), and the latest collection of essays, “The Death and Life of the Total Work of Art,” presented at the Bauhaus Colloquium in 2013, highlight the historic meaning of the term, and apply it to more recent events and works. Technological advancements provide the tools that allow for the creation of immersive artistic experiences, which remove “the borderline between object and observer, stage and audience, art work and spectator,”  university community, the concerts are mostly focused on the needs of the College of Architecture and Design population. The concert series directly supports several courses, including “Music for Designers,” which is focused on the theory and history of music, its relation to culture, and its use in cinema, digital and interactive media. Each concert is accompanied by a short lecture and PowerPoint presentation related to the theme of a concert, providing context as well as background information. Students design posters advertising the series. A book exhibition further enhances each event. The collaboration with musicians–a group of talented and dedicated educators–helps to develop programs that are both popular and educational. These events take place in an intimate “chamber-like” environment of the college Library which is located in the physical center of the building. Folding chairs that can be easily assembled form an auditorium. The Library remains open and fully functional during these events, which usually take place at night. Light refreshments help to create a pleasant and relaxing atmosphere. Free of charge, funded and supported by the college administration and alumni, these concerts have become popular and well attended. They help to alleviate stress, expand students’ horizons, improve their exposure to music, link performed musical compositions to the subjects of study in classes and studio, provide a historical context, and establish the Library as a place which can provide cultural and educational opportunities, often not possible within a curricular setting.

university community, the concerts are mostly focused on the needs of the College of Architecture and Design population. The concert series directly supports several courses, including “Music for Designers,” which is focused on the theory and history of music, its relation to culture, and its use in cinema, digital and interactive media. Each concert is accompanied by a short lecture and PowerPoint presentation related to the theme of a concert, providing context as well as background information. Students design posters advertising the series. A book exhibition further enhances each event. The collaboration with musicians–a group of talented and dedicated educators–helps to develop programs that are both popular and educational. These events take place in an intimate “chamber-like” environment of the college Library which is located in the physical center of the building. Folding chairs that can be easily assembled form an auditorium. The Library remains open and fully functional during these events, which usually take place at night. Light refreshments help to create a pleasant and relaxing atmosphere. Free of charge, funded and supported by the college administration and alumni, these concerts have become popular and well attended. They help to alleviate stress, expand students’ horizons, improve their exposure to music, link performed musical compositions to the subjects of study in classes and studio, provide a historical context, and establish the Library as a place which can provide cultural and educational opportunities, often not possible within a curricular setting.