The Twelve Books of Christmas

Lucy Campbell and Barbara Opar, column editors

Column by Barbara Opar

We think you will all agree that architects love books. There is still something satisfying about opening a new book for the first time. As you take off the shrink wrap, you look forward to settling down in a comfortable chair and flipping through the pages to revisit old topics or explore new material. There is the anticipation of wondering what images the author has selected and if they will be recognizable to you. Well, if all you want is a new book to peruse, then here are some suggestions you might give to Santa:

Adjaye, David. David Adjaye: Living Spaces. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2017. ISBN: 978-0500343258. 288 pages. $40.80

A dazzling tour of fifteen contemporary houses designed by David Adjaye, one of the most influential architects of his generation.

Houses or domestic buildings are often among the first projects young architects design. For David Adjaye, such early commissions connected him to a rising generation of creators with whom he shared a range of sensibilities. His artistry, clever use of space, and inexpensive, unexpected materials resulted in many innovative and widely published houses.

After fifteen years of practice and a raft of high-profile projects around the world_including the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC_houses represent a smaller portion of Adjaye’s work but are more potent as a result. Selecting projects that are challenging because of their sites, complexity, or architectural possibility, Adjaye has both expanded and sharpened his domestic design, taking it in new directions and to new locations.

This monograph presents the fifteen finest and most recent examples, from Africa to Brooklyn, from desolate farmlands to urban jungles. Chronicled through informed descriptions and detailed and photographically rich visual documentation, the results testify to the importance of Adjaye’s growing inventiveness and provide powerful ideas for residential architecture.

Bendov, Pavel. New Architecture New York. New York: Prestel, 2017. ISBN: 978-3791383682. 224 pages. $30.59

A magnificent photographic compilation of New York City’s best new architecture, this book features projects by leading firms working today. From Bjarke Ingels Group’s VIA West 57 to SHoP Architects’ Barclays Center, and from Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s High Line to SOM’s One World Trade Center, New York City has been home to some of this century’s most exciting new architecture. Profiling more than fifty projects that are shaping the city’s streets and skylines, this book features color photographs of each building and a brief, informative text about its significance. Renzo Piano Building Workshop, Ateliers Jean Nouvel, Foster + Partners, Selldorf Architects, Gehry Partners, and Adjaye Associates are just some of the firms that have recently completed projects in New York City. Visitors to the city as well as its denizens will find this book an exhilarating guide, while fans of architecture will gain an even greater appreciation of the city’s unprecedented development in the past fifteen years by the world’s best architects.

Emden, Cemal. Le Corbusier: The Complete Buildings. Munich: Prestel, 2017. 978-3791384023. 232 pages. $31.42

This visual tour of every one of Le Corbusier’s buildings across the world represents the most comprehensive photographic archive of the architect’s work. In 2010, photographer Cemal Emden set out to document every building designed by the master architect Le Corbusier. Traveling through three continents, Emden photographed all the 52 buildings that remain standing. Each of these buildings is featured in the book and captured from multiple angles, with images revealing their exterior and interior details. Interspersed throughout the book are texts by leading architects and scholars, whose commentaries are as fascinating and varied as the buildings themselves. The book closes with an illustrated, annotated index. From the early Villa Vallet, built in Switzerland in 1905, to his groundbreaking Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, completed in 1947, this ambitious project presents the entirety and diversity of Le Corbusier’s architectural output. Visually arresting and endlessly engaging, it will appeal to the architect’s many fans, as well as anyone interested in the foundation of modern architecture.

Glancey, Jonathan. What’s So Great About the Eiffel Tower?: 70 Questions That Will Change the Way You Think about Architecture. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2017. ISBN: 978-1780679198. 176 pages. $12.80

Why do we find the idea of a multi-colored Parthenon so shocking today? Why was the Eiffel Tower such a target for hatred when it was first built? Is the Sagrada Família a work of genius or kitsch? Why has Le Corbusier, one of the greatest of all architects, been treated as a villain?

This book examines the critical legacy of both well known and either forgotten or underappreciated highpoints in the history of world architecture. Through 70 engaging, thought-provoking, and often amusing debates, Jonathan Glancey invites readers to take a fresh look at the reputations of the masterpieces and great architects in history. You may never look at architecture in the same way again!

Goldberger, Paul. Building Art: The Life and Work of Frank Gehry. New York: Vintage, 2017. ISBN: 978-0307946393. 544 pages. $13.49

Here, from Pulitzer Prize–winning critic Paul Goldberger, is the first full-fledged critical biography of Frank Gehry, undoubtedly the most famous architect of our time. Goldberger follows Gehry from his humble origins—the son of working-class Jewish immigrants in Toronto—to the heights of his extraordinary career. He explores Gehry’s relationship to Los Angeles, a city that welcomed outsider artists and profoundly shaped him in his formative years. He surveys the full range of his work, from the Bilbao Guggenheim to the Walt Disney Concert Hall in L.A. to the architect’s own home in Santa Monica, which galvanized his neighbors and astonished the world. He analyzes his carefully crafted persona, in which an amiable surface masks a driving ambition. And he discusses his use of technology, not just to change the way a building looks, but to revolutionize the very practice of the field. Comprehensive and incisive, Building Art is a sweeping view of a singular artist—and an essential story of architecture’s modern era.

Mayne, Thom. 100 Buildings. New York: Rizzoli, 2017. ISBN: 9780847859504. 264 pages. $17.00

For this volume, over forty internationally renowned architects and educators—from Peter Eisenman and the late Zaha Hadid to Rafael Moneo and Cesar Pelli—were asked to list the top 100 twentieth-century architectural projects they would teach to students. The contributors were encouraged to select built projects where formal, spatial, technological, and organizational concepts responded to dynamic historical, cultural, social, and political circumstances. The capacity of these buildings to resist, adapt, and invent new typologies solidifies their timeless relevance to future challenges.

Olonetzky, Nadine. Inspirations: Time Travel Through Garden History. Basel: Birkhauser Architecture, 2017. ISBN: 978-3035613841. 206 pages. $39.99

Every garden is an imagined paradise a garden paradise that incorporates the personality of the individual who created it, but also the long history of horticulture.

The book recounts the history of gardens from their likely origins in Mesopotamia to today; in chronological order and in sections with keywords, it introduces the most important styles as well as the people that have influenced developments in Europe.

Although the famous and influential gardens often needed extensive funds for their creation, gardens are not designed for the privileged of this world. Whether it is an allotment, a landscape park, a cemetery, or a city park small and large gardens interweave with the built landscape and are an inspiration for all of us.

Paul, Stella. Black: Architecture in Monochrome. New York: Phaidon Press, 2017. ISBN: 9780714874722. 224 pages. $37.84

A stunning exploration of the beauty and drama of 150 black structures built by the world’s leading architects over 1,000 years. Spotlighting more than 150 structures from the last 1,000 years, Black pairs engaging text with fascinating photographs of houses, churches, libraries, skyscrapers, and other buildings from some of the world’s leading architects, including Mies van der Rohe, Philip Johnson, and Eero Saarinen, David Adjaye, Jean Nouvel, Peter Marino, and Steven Holl.

Rau, Cordula. Why Do Architects Wear Black? Basel: Birkhauser Architecture, 2017. ISBN: 9783035614107. 260 pages. $22.99

Why is it really that architects wear black?” was a question put to Cordula Rau by an automotive industry manager during an architectural competition. Even though she herself is an architect, and wears black, she did not have an answer on the spot. So she decided to ask other architects, as well as artists and designers. She has been collecting their handwritten replies in a notebook since 2001.

In 2008, this collection of autographs appeared as a small publication obviously bound in black. For the purpose of the new edition, this legendary collection was expanded by new notable, amusing, pragmatic, and quirky reasons: “Please read it and don’t ask me why architects wear black!”. (Cordula Rau)

Ryan, Zoe. As Seen: Exhibitions that Made Architecture and Design History. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2017. ISBN: 978-0300228625. 144 pages. $30.49

Exhibitions have long played a crucial role in defining disciplinary histories. This fascinating volume examines the impact of eleven groundbreaking architecture and design exhibitions held between 1956 and 2006, revealing how they have shaped contemporary understanding and practice of these fields. Featuring written and photographic descriptions of the shows and illuminating essays from noted curators, scholars, critics, designers, and theorists, As Seen: Exhibitions that Made Architecture and Design History explores the multifaceted ways in which exhibitions have reflected on contemporary dilemmas and opened up new processes and ways of working. Providing a fresh perspective on some of the most important exhibitions of the 20th century from America, Europe, and Japan, including This Is Tomorrow, Expo ’70, and Massive Change, this book offers a new framework for thinking about how exhibitions can function as a transformative force in the field of architecture and design.

Stech, Adam Sally Fuls and Robert Klanten.; Inside Utopia: Visionary Interiors and Futuristic Homes. Berlin: Gestalten, 2017. ISBN: 9783899556964. 288 pages. $46.91Top of Form

Spectacular and reflective, unpretentious and efficient: the breathtaking Elrod House by John Lautner; the Lagerfeld Apartment near Cannes that seems like a set from a science fiction film; Palais Bulles in France with its organic and unique architecture. These interiors welcome habitation and spark curiosity while embodying the foundations of minimalism and bygone visions of the future. Inside Utopia delves into the rhyme and reason behind past designs that we still interact with today.

The architects, the owners, and the craftsmen like Gio Ponti or Bruce Goff who work behind the scenes created amorphous interiors that invite the mind to wander. At the time they were futuristic, confident, utopian, idealistic— we may not realize it, but they have shaped our current living concepts, and even now, they inspire us anew. Previously it has been difficult to attain access to these preserved interiors, but Inside Utopia unearths what was before unseen.

Yeang, Ken. It’s Not Easy Being Green. Novato: ORO Editions, 2017. ISBN: 978-1939621863. 100 pages. $25.23

It’s Not Easy Being Green, literally tells the reader that the idea of ‘Green architecture’ is not as simple as many expected. It’s not solely about energy efficiency or putting out different levels of vegetation, but it is an extensive dedication and cautious action towards natural and built environment. Ken’s work has demonstrated a comprehensive set of strategies making Green Architecture feasible and practical for architects and professionals from other fields to understand the importance of saving the world from environmental devastation. The book intends to raise awareness and concern on environmental issues, and suggests ways of how architecture can be design now in favor of a benign living environment.

See anything you like? Hope so! Obviously this list is just a small sampling of newly released titles and many of you may have specific ideas about the books you want to add to your collections. But if you need further suggestions, take a look at your library’s new book display or site. You can even ask your subject librarian! Either way, enjoy a little downtime with your favorite new book.

Study Architecture

Study Architecture  ProPEL

ProPEL

Camilla Leach was born in New York in 1835, and following college, traveled west. She obtained teaching assignments in French or art in Chicago, then in California’s Bay Area, and in Oregon became head of a private school in Portland. In 1895, Miss Leach was employed by the University of Oregon in Eugene as a registrar while also serving as the university’s librarian. The university, only twenty years old at this time, had a small library collection that was relocated several times before the first purpose-built library opened in 1906. Resistant to retiring, and beloved by faculty and students, Miss Leach worked in the new library until 1914 when, at the age of 79 years, she transferred to the new School of Architecture and Allied Arts, where she served as librarian and clerical assistant for the next ten years. In his moving commemoration of the respected Miss Leach, who died in 1930, Dean Lawrence noted that she was in the process of translating Auguste Racinet’s L’Ornement Polychrome (Paris, 1869-73) for the benefit of the students.

Camilla Leach was born in New York in 1835, and following college, traveled west. She obtained teaching assignments in French or art in Chicago, then in California’s Bay Area, and in Oregon became head of a private school in Portland. In 1895, Miss Leach was employed by the University of Oregon in Eugene as a registrar while also serving as the university’s librarian. The university, only twenty years old at this time, had a small library collection that was relocated several times before the first purpose-built library opened in 1906. Resistant to retiring, and beloved by faculty and students, Miss Leach worked in the new library until 1914 when, at the age of 79 years, she transferred to the new School of Architecture and Allied Arts, where she served as librarian and clerical assistant for the next ten years. In his moving commemoration of the respected Miss Leach, who died in 1930, Dean Lawrence noted that she was in the process of translating Auguste Racinet’s L’Ornement Polychrome (Paris, 1869-73) for the benefit of the students.

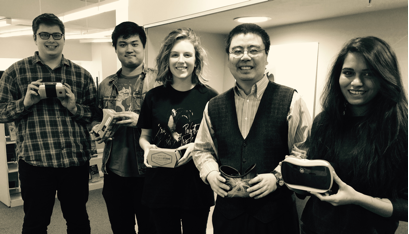

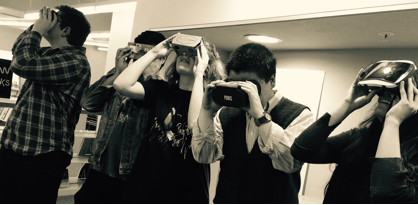

Elizabeth Feltz, a 4th year undergraduate (B.S. Arch) is working on a project that aims to show how mixed reality technology can affect early childhood education and learning environments. Her site is the Grixdale Neighborhood of Detroit, an area that has suffered from significant population decrease and increased crime. Her project proposes renovation of an existing elementary school in the Grixdale neighborhood to create classrooms in response to virtual reality experiences of the children of the school. Parents can use VR as a tool to engage with actual space and educate their children at home. The VR classrooms will be ‘lab spaces’ where children use the software to interact with community members, creating a more unified, safe, and healthy learning environment.

Elizabeth Feltz, a 4th year undergraduate (B.S. Arch) is working on a project that aims to show how mixed reality technology can affect early childhood education and learning environments. Her site is the Grixdale Neighborhood of Detroit, an area that has suffered from significant population decrease and increased crime. Her project proposes renovation of an existing elementary school in the Grixdale neighborhood to create classrooms in response to virtual reality experiences of the children of the school. Parents can use VR as a tool to engage with actual space and educate their children at home. The VR classrooms will be ‘lab spaces’ where children use the software to interact with community members, creating a more unified, safe, and healthy learning environment. Tanvi Shah, (M.Arch 2018), is attempting to solve an existing problem in many American cities – the death of downtown after 6pm. Through the use of kinetic and modular architecture combined with mixed reality, her project in downtown Cincinnati responds to this problem through creation of a building that changes function in an 8-hour cycle over a period of 24 hours to ensure continued use. Her concept works at two scales – architectural and individual. The architectural component of the project is important as it provides the user haptic feedback, making the VR experience more immersive. The individual component is the user’s VR headset. This allows users to customize the space and create environments to enhance their productivity.

Tanvi Shah, (M.Arch 2018), is attempting to solve an existing problem in many American cities – the death of downtown after 6pm. Through the use of kinetic and modular architecture combined with mixed reality, her project in downtown Cincinnati responds to this problem through creation of a building that changes function in an 8-hour cycle over a period of 24 hours to ensure continued use. Her concept works at two scales – architectural and individual. The architectural component of the project is important as it provides the user haptic feedback, making the VR experience more immersive. The individual component is the user’s VR headset. This allows users to customize the space and create environments to enhance their productivity.