Where Are My People? Black in Architecture

Where Are My People? Black in Architecture

Kendall A. Nicholson, Ed.D., Assoc. AIA, NOMA, LEED GA

ACSA Director of Research and Information

August 14, 2020

In the area of racial diversity, it is commonly known that representation, or the lack thereof, is a discipline-wide issue. Where Are My People? is a research series that investigates how architecture interacts with race and how the nation’s often ignored systems and histories perpetuate the problem of racial inequity. Inspired by the data visualizations created by W.E.B. Du Bois in 1900, the first research report in the series, Black in Architecture, highlights metrics to help both the profession and the academy understand what it means to navigate architecture as a Black person.

In the wake of the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor, many have turned their attention to the underpinning of race across various realms of society. ACSA is continuing to learn, listen, and ask questions. Asking “why” is imperative.

Why is it that Black people are less likely to choose architecture than other service professions like medicine or education? Why is it that many architecture departments have no Black faculty members? Why is it that architecture schools have difficulty attracting and retaining Black students? To start, let’s consider the historical context.

Since its inception, architecture has been designed by and for White men of an elite social class. That being considered, the story of Blacks in America starts in 1619 with the Transatlantic Slave Trade. For the next 246 years, America’s prosperity was contingent on the vile and heinous system of chattel slavery where Blacks belonged to Whites and, as property, became the inherited wealth of colonizers and were denied the opportunity to build generational wealth for themselves. Following the Emancipation Proclamation in 1865, Blacks in America spent another 99 years being “free” from ownership but not free from discrimination. It was during this time that Blacks gained the ability to learn to read and write but were criminalized by the convict leasing and peonage systems, segregated by red-lining policies, and subject to underfunded schools, spaces and infrastructure. This widespread overt discrimination was outlawed with the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but the consequences of many of those policies still linger.

Data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) show that 1 out of every 33 Black men over the age of 18 is serving a prison sentence. For White men of the same age bracket, the ratio jumps to 1 out of every 251. That disparity is made greater when the US Census reports that Black men only comprise 6% of the US population, but the BJS reports that Black men make up 32% of the prison population. It is with this context that we digest that approximately 1.5% of licensed architects are Black men. While valiant efforts to recruit and retain Black students should be commended, it is imperative to understand that the lack of Black men in architecture schools is a symptom of a larger systemic problem: The criminalization of Black men. How can we expect to increase the number of Black male students in the architecture pipeline when so many Black fathers and sons fall subject to hyper-policing and policies that were created to put them in prison?

Analyzing the pipeline for Black women in architecture shows the conflation of race and gender leading to significant issues of representation in the profession. The saying “You can’t be what you don’t see” rings true. Only 1.9% of architecture degrees accredited by the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) or considered pre-professional were earned by Black women. Moreover, while Black women make up nearly two-thirds (63%) of all Black students in higher education, they make up just 34% of all Black architecture students across all degree types and school types, i.e. to include two-year colleges. These statistics indicate that in most scenarios, Black women are tasked with forging their own path through the academy into the profession.

A deep dive into where Black students find themselves in the academy uncovered the significant role Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) play in recruiting Black students to architecture. Of the 139 NAAB accredited schools of architecture, 7 are HBCUs. Those 7 schools – Florida A&M University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morgan State University, Prairie View A&M University, Tuskegee University, and the University of the District of Columbia – make up 5% of the NAAB accredited schools but enroll 32% of the total Black student population in accredited and preprofessional programs. Said differently, 1 out of every 3 Black architecture students attends an HBCU. This is substantial, because, on average, each of the remaining degree programs only graduates 2 Black architecture students each year.

For the past 11 years, NAAB has reported that Black students enrolled in NAAB-accredited programs make up 5% of the student population. That number remains steady. While it’s evident that metric is not increasing, it is also important to note the relationship between NAAB-accredited programs and their preprofessional counterparts. In 2019, NAAB reported that, much like every other year, Black students made up 5% of the students enrolled in NAAB-accredited programs. However, Black students also made up 10% of the students enrolled in preprofessional programs. These data show that not only do Black students take up a larger share of the preprofessional student population but that there are more Black students enrolled in preprofessional programs than NAAB-accredited programs across the country. Tuition statistics in the ACSA Institutional Data Report indicate that the cost of undergraduate education is lower and thus more accessible. The issue is that licensure requirements for 38 of the 55 jurisdictions hold graduation from a NAAB-accredited program as a requirement for licensure. This means that more Black students are ineligible for licensure than are eligible just by degree choice alone.

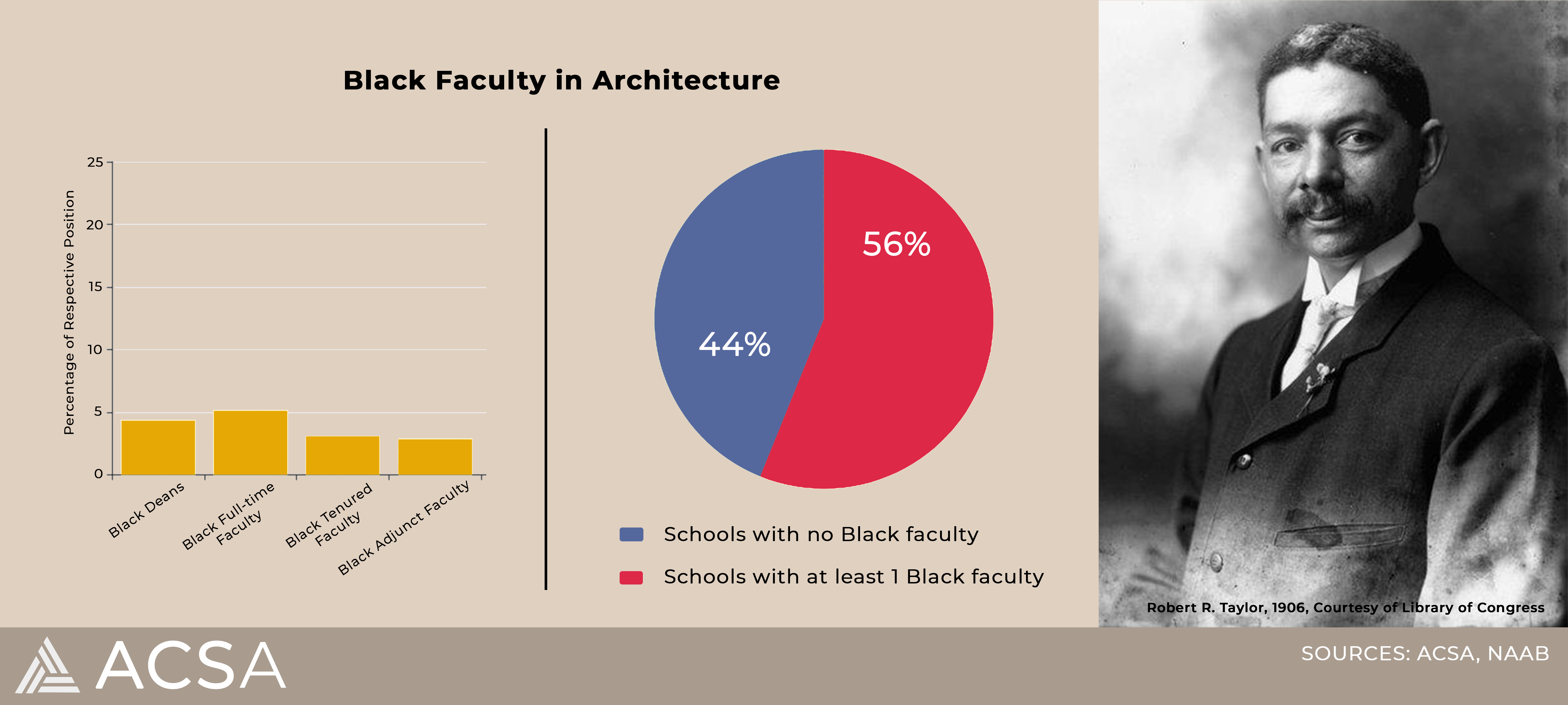

Pictured above is Robert R. Taylor, one of the first Black leaders of an architecture school. He is noted to be the first Black graduate from MIT’s architecture program in 1892 and later went on to establish the architecture program at Tuskegee Institute at the turn of the century.

The disproportionately low number of Black architecture students is mimicked in the architecture faculty. Research on this topic showed a little less than half (44%) of the architecture schools did not have one Black faculty member in the department. Black full-time faculty make up 5% of all full-time faculty, and Black full-time tenured faculty make up 3% of all tenured faculty. With just under 100 architecture school deans, our records indicate that 4 identify as Black/African American making up 4% of the deans at ACSA member schools. Anecdotally, adjunct faculty are thought to be more racially diverse than full-time faculty, but, in this case, the data shows just the opposite. Only 2.8% of the adjunct architecture faculty across the country identified as Black/African American.

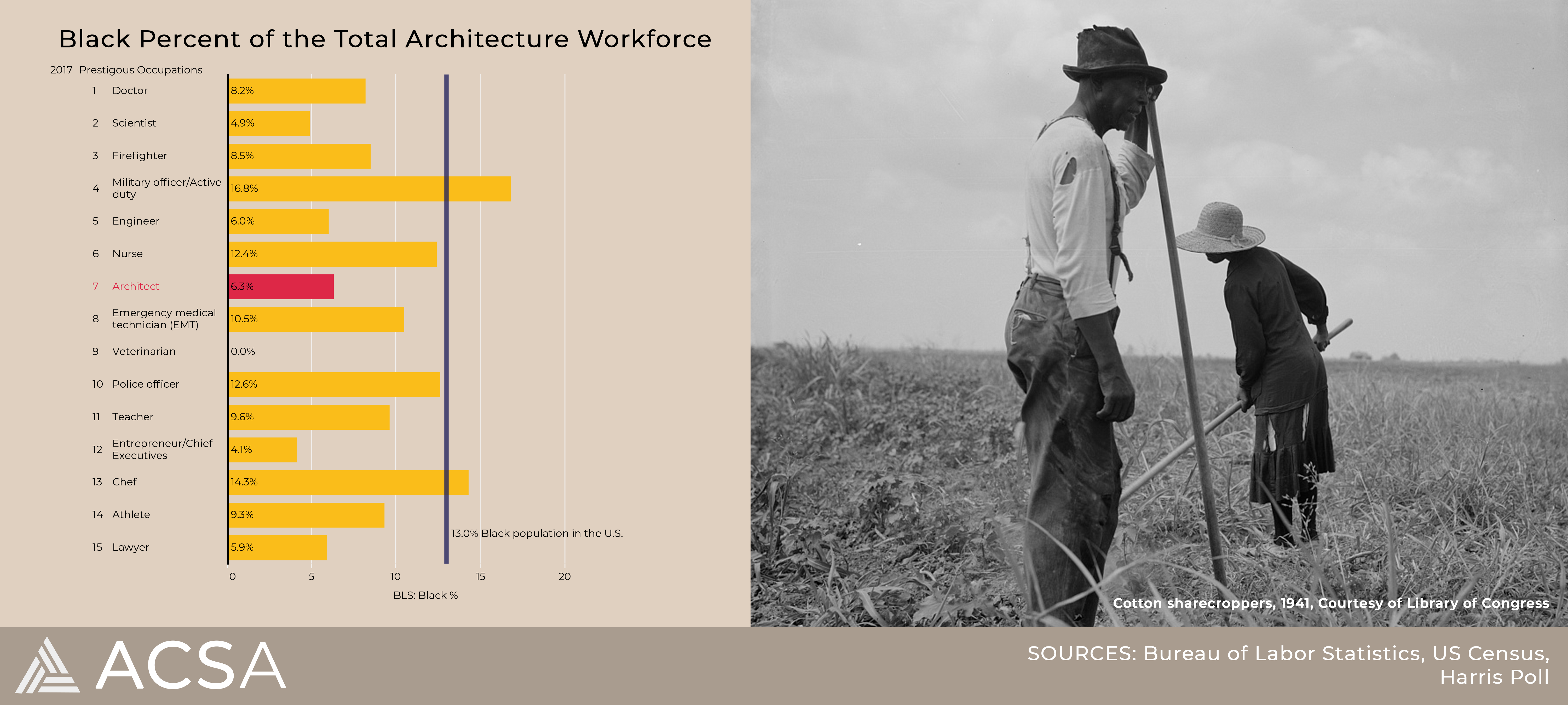

Every 2 or 3 years, the Harris Poll conducts a survey of the most prestigious occupation as perceived by Americans across the country. Architects have made the list in almost every iteration of the survey. In 2017, architects ranked seventh on the list following other mainstay professions such as doctors, firefighters and nurses. While architects are known as notable and prestigious professional members of society, they are not often perceived as socially relevant. Of the top 15 prestigious occupations, architects came in tenth place if ranked by the percent of Black workforce in the profession. Just like the statistics across the academy, these data beg the questions “Who is architecture serving?” and “Who is represented?”. One common discussion point among architects is how other similarly situated professions such as physicians, attorneys, and engineers diversify their workforce. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, attorneys and engineers have less Black representation than architects, but physicians have more. Is there something medicine is doing that architecture could learn from?

Quite similar to the case for women in architecture, data in recent years show an increase in Black people being awarded architecture’s highest honors (AIA Gold Medal, AIA/ACSA Topaz Medallion, Pritzker Prize, and ACSA Distinguished Professor). Each award has a longstanding history of being awarded to predominately White men, with the ACSA Distinguished Professor designation being the most diverse. Of the 360 honors awarded since 1907 only 3, less than 1%, have been awarded to Black people. Sharon Egretta Sutton, Professor Emerita at the University of Washington, was the first to get one of the four awards, receiving the ACSA Distinguished Professor award in 1996. Thomas Fowler IV, Professor at California Polytechnic State University – San Luis Obispo, was the second to receive the ACSA Distinguished Professor award in 2011. And Paul Revere Williams was the first Black person to receive the AIA Gold Medal, which was awarded posthumously in 2017. What does it mean that the work of Black architects is rarely elevated as worthy of awards?

The research above follows the current metrics of evaluating equity in the field of architecture and illuminates the disenfranchisement of Black architects and designers. For four centuries Blacks in America have been plagued by intentional programs, policies and procedures that negatively affected their ability to gain access to both the profession and the academy. The data presented acknowledges the longstanding history of Whiteness and the myth of a meritocracy which has excluded Black people for far too long. It is important to recruit more Black students and to hire more Black faculty. It is important to give voice to the Black architects and designers in firms across the country. It is important to acknowledge the harm that has been done in the built cityscapes architects create. It will be important that we work collectively to make changes to the systems of housing, policing, education and the like if we want to see change on the ground.

Questions

Kendall Nicholson, Ed.D.

Director of Research + Information

202-785-2324

knicholson@acsa-arch.org

Study Architecture

Study Architecture  ProPEL

ProPEL