Lucy Campbell and Barbara Opar, column editors

Column by Amy Trendler, Architecture Librarian, Ball State University Libraries, aetrendler@bsu.edu

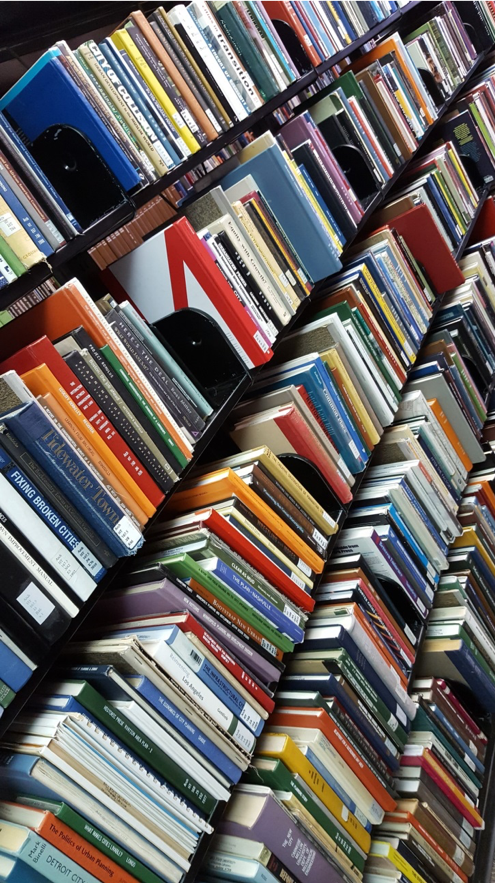

It’s the end of another academic year and the library shelves are likely looking pretty crowded. Libraries that support disciplines like architecture, where physical books and design magazines continue to be essential, often face a shortage of shelf space. As a result, summer is a popular time for librarians to engage in collection review, identify books to remove or transfer, and alleviate the overcrowding on the shelves. Typically, titles with low circulation rates and older publication dates are closely scrutinized to determine if the book is outdated or no longer relevant to the library collection. Second copies and earlier editions are also prime candidates for review, which may lead to the removal of one item and the retention of a duplicate or similar item. However, there is such a dire space crunch in some libraries that reviewing and removing a portion of the books in any or all of these categories does not significantly impact the size of the collection. When that’s the case, librarians have to identify additional criteria for review.

This was the situation in our library after we completed collection reviews for second copies, earlier editions, little-used or outdated titles and then discovered that we were still left with overcrowded shelves. After asking librarian colleagues for advice, reading articles like Janine Henri’s August 2017 article in this column (“Struggling with Space: Collection Browsing, Architectural Illustrations, and Remote Storage Decisions,” on the UCLA Arts Library’s review process) with great interest, and considering our options, I began reviewing the library’s collection based on additional criteria that fit our particular situation. My takeaway from the process is that planning for such a collection review should start with considering all the variables that define the library or the project at hand. These include the library mission, the curriculum, the time available for the collection review, timing of any planned changes to the space, staff availability, consortia agreements, offsite storage, the possibility of transferring titles to other libraries on campus, access to reports and collections data, and any upcoming changes to administration, faculty, or curriculum that could affect the focus of the collections. By looking closely at these variables, it is possible to plan a collections review that goes beyond basic collections data about checkouts and date of publication.

This was the situation in our library after we completed collection reviews for second copies, earlier editions, little-used or outdated titles and then discovered that we were still left with overcrowded shelves. After asking librarian colleagues for advice, reading articles like Janine Henri’s August 2017 article in this column (“Struggling with Space: Collection Browsing, Architectural Illustrations, and Remote Storage Decisions,” on the UCLA Arts Library’s review process) with great interest, and considering our options, I began reviewing the library’s collection based on additional criteria that fit our particular situation. My takeaway from the process is that planning for such a collection review should start with considering all the variables that define the library or the project at hand. These include the library mission, the curriculum, the time available for the collection review, timing of any planned changes to the space, staff availability, consortia agreements, offsite storage, the possibility of transferring titles to other libraries on campus, access to reports and collections data, and any upcoming changes to administration, faculty, or curriculum that could affect the focus of the collections. By looking closely at these variables, it is possible to plan a collections review that goes beyond basic collections data about checkouts and date of publication.

Considering the variables begins to help define their impact on the collection and the implications for the collection review. To take just one example, the library mission statement—whether it is formal or informal—usually describes the library’s user groups and the subjects covered by the collection. The impact might be that any subjects not explicitly included in the mission should be closely reviewed and removed from the collection to be transferred to offsite storage, a main library or other branch library in the system, or withdrawn from the collection altogether. In the case of an architecture library that collects materials in architecture and landscape architecture, books about any topic outside of those two areas, such as art, history, or geography, are candidates for thorough review and possible removal from the architecture library’s collection. Collections data—number of checkouts, date of last checkout, and date of publication—are still factored in, but the range for each of these categories should be set so that they are more expansive than they would be for books in the primary subject areas. For instance, if 0-3 checkouts is the range used to identify books to review for architecture and landscape architecture, then 0-10 or higher should be the range for books on secondary subjects. The same is true when considering consortial agreements. If another library in the consortia is designated as the repository for art or history or geography, then titles in these areas should be more closely reviewed even if offsite storage or transfer are not options.*

In addition to identifying criteria for items to scrutinize and potentially remove, planning for the collection review can also cover which items to keep on the library’s shelves. Depending on the variables, it may be important to prioritize the on-site retention of professional publications, well-illustrated titles (as described in Henri’s article), books intended primarily for an undergraduate or graduate audience, English-language publications, or books closely related to the curriculum or faculty interests. As in many architecture libraries, collections review will continue to be ongoing for us, but by continuing to be thoughtful about the variables I am confident that our reviews will achieve the intended result—a focused, useful, and up-to-date collection that comfortably fits in the space available for it.

*There is software available to help with collection review and comparison between collections. In addition to library systems’ report capabilities, a product such as OCLC’s GreenGlass is designed to assess library collections individually or in consortia.

Study Architecture

Study Architecture  ProPEL

ProPEL