Free Web-based Resources to Add to Your Quiver of Tricks over the Summer

Barbara Opar and Barret Havens, column editors

Column written by Barbara Opar

Summer is officially here! And with it, nice weather (hopefully), home chores, travel plans and just maybe–a little time to catch up on some reading or update your skill set in preparation for another busy fall. There may be a backlog of specialized publications for you to plow through during your summer “down time” (is there really such thing in academia?) from departmental newsletters to targeted scholarly journals–let alone more general sources like The Chronicle of Higher Education. Despite that, AASL would like to recommend a few more resources. You may or may not be familiar with them but we believe they will be invaluable to you in terms of keeping up with trends and developments in architecture and design-related disciplines as well as preparing for yet another busy semester of teaching, research and academic ventures.

Architecture Week & ArchInnovations

In terms of general overviews of goings-on in the profession, Architecture Week continues to be a vital resource. Another perhaps lesser known source is ai (ArchInnovations), an online magazine which features information about–and reviews of–new buildings, as well as events, archived projects, and books.

ARLIS/NA Multimedia & Technology Reviews

A bi-monthly publication of the Art Libraries Society of North America, ARLIS/NA Multimedia & Technology Reviews target projects, products, events, and issues within the broad realm of multimedia and technology related to arts scholarship, research, and librarianship.

Social Media Site for the Architecture Professional

Want to post the best of your student work? Architizer is a social-networking web site that allows architects to swap news, showcase their portfolios and, most importantly, get their work in front of architecture buffs and potential clients. In a sense, it functions like Facebook for architects.

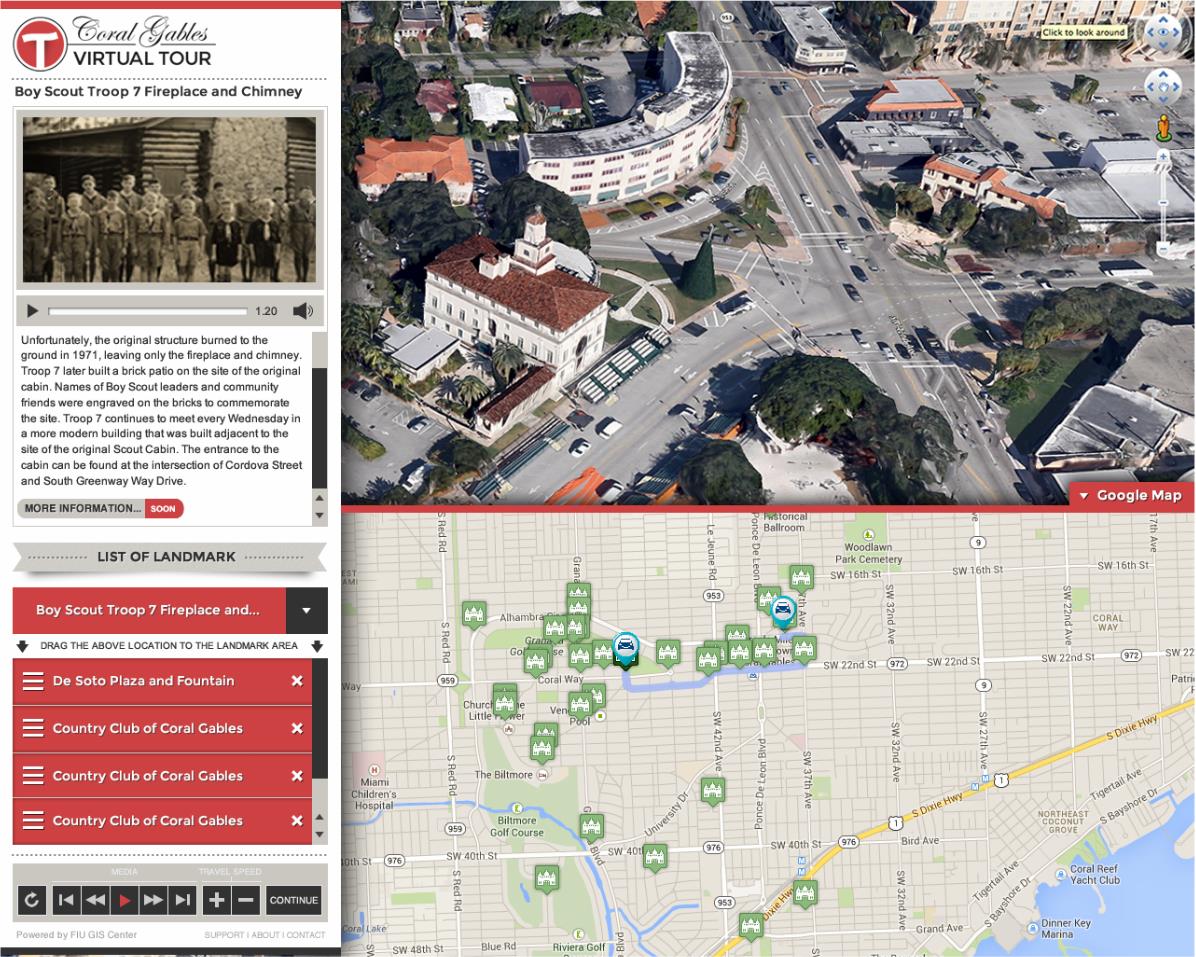

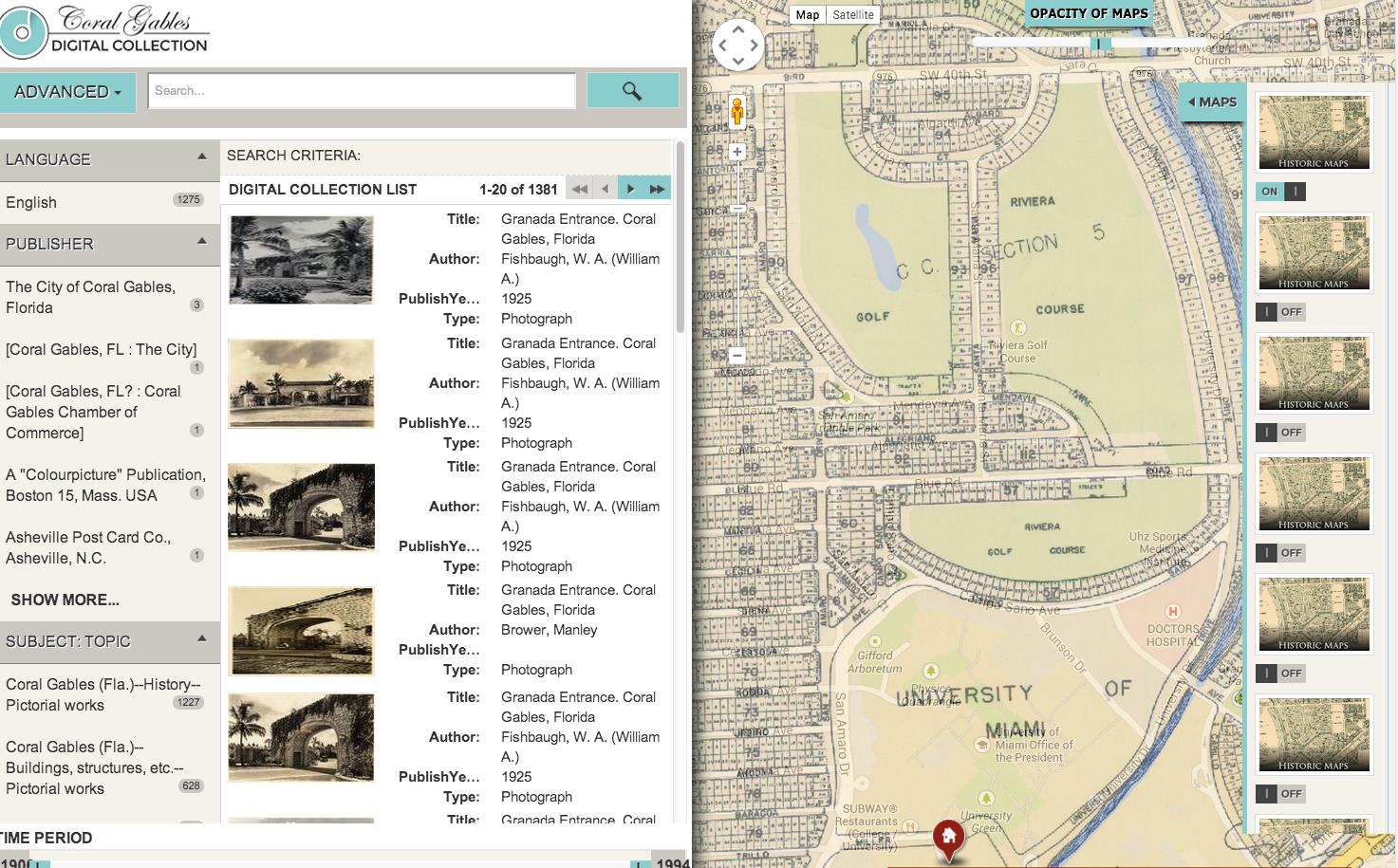

Digital Collections

Digital collections abound. Often drawn from archival collections, these sites provide a wealth of information and serve to aid the researcher looking for overviews as well as the professional designer needing to incorporate images. The Society of Architectural Historians lists notable projects on its site. Also consider public library collections when researching major urban centers. Public libraries like New York Public Library have substantial digital collections.

Geospatial Data

Looking to use more geospatial data in your design teaching? Check out Earthworks, which features downloadable geospatial data sets from across the world contributed by multiple academic institutions, available via Stanford University’s EarthWorks portal. Go-Geo is another useful source of this type.

Planetizen

Focusing your work on urban design? Planetizen is a public-interest information exchange for the urban planning, design, and development community. It labels itself a one-stop source for urban planning news, editorials, book reviews, announcements, jobs, education, and more. Coverage includes infrastructure, climate change, and historic preservation.

Preservation

Interested in preservation topics? The National Trust for Historic Preservation publishes a blog consisting of stories, news, and notes.

Sustainability

Sustainability takes many forms and there are many online resources. A couple notable examples include Ecotecture, the Journal of Ecological Design and Energy Design Resources which presents tools, articles and media covering a broad base of topics within the overall genre of green building and design.

Material Resource

Finally, another site published by the Art Libraries Society of North America (ARLIS/NA), Material Resource, the blog for materials collections in art, architecture, and design environments brings together events, resources and postings about specific collections topics.

We hope you will explore these sites and find new and useful information to prepare you for a productive academic year. Need more? Your University’s architecture or design librarian and AASL member will be willing and able to help.

Study Architecture

Study Architecture  ProPEL

ProPEL