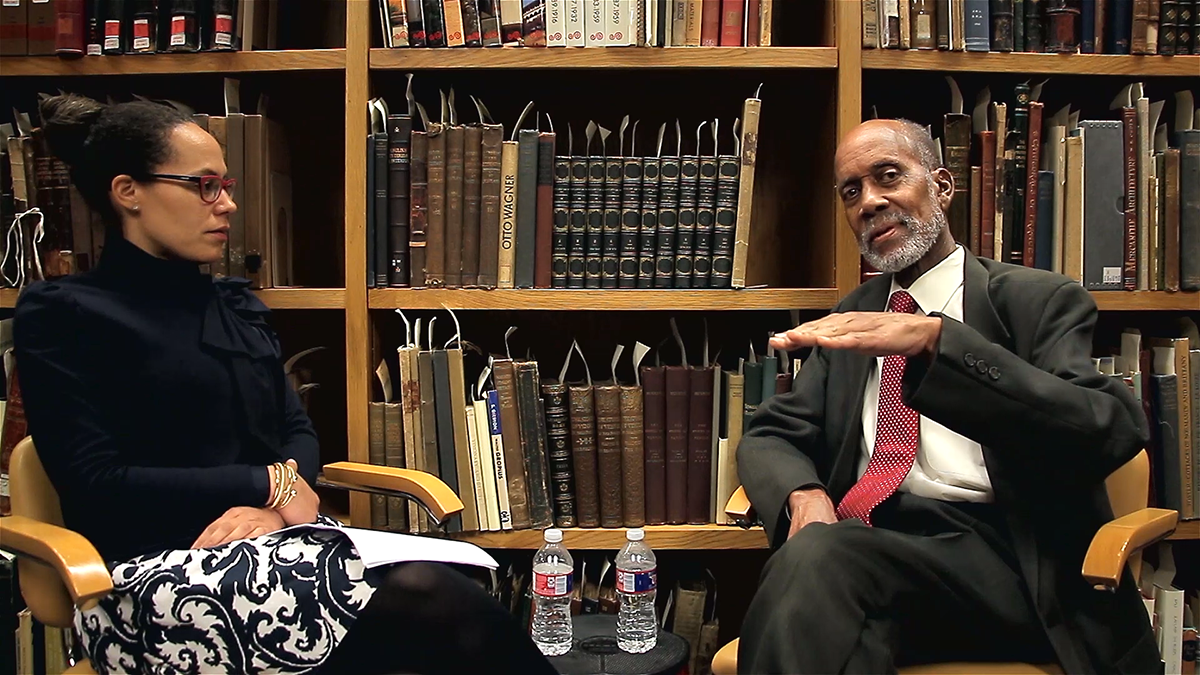

Archivist Danielle Burns Wilson interviews retired architect Wilbert O. Taylor for the Building Houston collection

Effective Strategies for Architectural Oral Histories: Building Houston

by Catherine Essinger, University of Houston

Lucy Campbell and Barbara Opar, column editors

Local architecture can be a difficult topic for students to research. Buildings that loom large in a region do not always have the same presence in architectural publications. Architectural literature may offer little more than building graphics. Buildings are more than their design elements, but the social, political, and historical considerations that surround those buildings may be hidden in archives and other resources of which most undergraduate students are unaware. This is particularly true when students research local buildings by local architects who lack a national presence. The stories that can help researchers understand design decisions may only exist in the memories of the people involved in their creation.

The elusiveness of local architecture is a challenge for the staff of the William R. Jenkins Architecture, Design, and Art Library at the University of Houston. Students and members of the public regularly request information about local buildings, hoping to find more than plans. Houston’s propensity for constant redevelopment means that most of its built environment is relatively contemporary. Much of it is neither well-documented nor archived. Local architects and their associates may be the only source of information for the context of and influences on their design decisions. This convergence of challenges is also common in other cities and an impediment to architectural research.

In order to capture the vanishing narrative of Houston’s built environment, the Jenkins Library staff launched an oral history project called Building Houston that focuses solely on the buildings and designed spaces. The goal of the project is to tell the story of Houston’s designed spaces and how they came to be. That narrative is told from the perspective of architects, engineers, developers, educators, and others who have impacted it. The project developed slowly and with many readjustments. The organizers had to compensate for insufficient time, experience, and infrastructure in order to create this growing collection of 35 recordings now housed on the University of Houston Libraries’ audiovisual repository (av.lib.uh.edu). This column will present the steps that proved most effective in building an architecture-specific oral history collection, learned through trial and error, for educators who wish to establish their own.

Infrastructure

Platform

A stand-alone website could suffice, but discoverability was significantly increased by loading Building Houston onto a shared platform. Most universities now have open repositories for digital collections. Search engines and databases harvest content from these platforms. Search terms will also lead library catalog users directly into the repository, so even someone unaware that the digital collection exists can stumble across it when searching a building or architect by name.

Technical equipment and training

After several less than perfect recordings, the staff realized that more attention should be paid to the technical aspects of the project. Commonplace equipment resulted in muddy audio. The staff petitioned for professional-quality video cameras and lights. Access to audiovisual equipment and a new employee with technical experience resulted in recordings of notably higher quality. The more recent recordings, therefore, are viewed longer and more often.

Partnerships

Institutions with complimentary online platforms help promote the collection and encourage others to share their stories. The library has worked closely with the local chapter of the American Institute of Architects to develop Building Houston. The chapter’s Historic Resources Committee was extremely helpful in identifying interview subjects and serving as interviewers. The committee also hosts the interviews on its webpage. Another institutional partner is the Houston Public Library system, which boasts a massive oral history collection dedicated to local people and experiences. The public library system welcomed the addition of Building Houston interviews to its platform. These organizations both create a link within their sites that links directly into the repository page containing a specific recording.

Creating a space conducive to recording

The first recordings usually took place in the home of an interview subject, but those environments were difficult to control. Despite requests for quiet, these interviews were interrupted by phones and visitors. In one, a wood-paneled wall produced such a glare that it took a team of video production students 40 minutes to mute the reflection. For the last three years all interviews have been recorded in the library’s rare books room, which offers quiet, non-reflective surfaces, and a locked door.

All subjects and interviewers now also receive guidelines when they agree to participate, which include the following technical requirements:

- Recordings should take place is a confined space where the noise may be controlled.

- All noise-making devices (phones, clocks, etc.) should be silenced during the taping.

- Interviewer and subject should be placed approximately the same distance from the microphone(s).

- A sound check must be conducted before the interview begins, which allows the recorder to make the best recording possible.

- At the beginning of the recording, the recorder will state his/her name and location and introduce the participants. When the recorder introduces you, you will speak, so listeners will associate your voice with your name. When the recorder introduces the subject, they will also say something for the same reason.

Interviewer training

The people who share their stories in Building Houston are welcome to select their own interviewer. This helps the subjects communicate comfortably. Interviewing is, however, more work and more complicated. Interviewers should be given clear written guidelines and good examples to follow. Building Houston interviewers are asked to perform the following tasks before the recording.

- Research your subject before the interview.

- Make a chronological list of his/her major projects to which you may refer during your interview. This will help you stay on track.

- Ask your subject to suggest stories and subjects you may wish to include in the recording. Subjects are encouraged to help plan their own interviews.

- Consult archival collections for information.

- Ask your subject if they have files, portfolios or other materials that may help you organize your interview questions in advance.

- Create a list of questions before the interview in order to ensure an organized, efficient recording.

- Run through the questions with your subject or a surrogate ahead of time to help gauge the recording time required.

This preparation usually leads to trouble-free recordings.

Content

Thematic focus

While the project organizers always intended to gather information about Houston architecture, they did not always communicate that goal to subjects and interviewers effectively. Because oral histories are normally stand-alone recordings documenting personal experience, many people understandably focused more on personal narrative than built work. Many personal details are certainly pertinent to the study of local architecture. Architect Eugene Aubry, for example, tied childhood stories to his professional output when he described how school architecture in his native Galveston influenced his own style. Some interviewers dedicated time to matters that were extraneous to Houston architecture, however. To mitigate this tendency, the library staff inserted the goal of creating a narrative around Houston’s built environment into every section of the guidelines and reiterated this point with interviewers verbally. Because the interview subjects are typically architects and other professionals outside academia, it is also helpful to explain the scholarly uses of the collection, so they better understand what information is sought.

Controversial content

Some interviews are unexpectedly frank. One architect spoke about bribing politicians for commissions. Another complained about a former colleague in very personal terms and spoke disparagingly about his children. Any statements that are licentious, offensive, or otherwise inappropriate may be edited. It is best, however, to avoid them from the beginning. The guidelines now include the following statement: “Please remember that this oral history will be posted online and viewed by many people. Content that is licentious or offensive will not be accepted into the Digital Library. If such content appears intermittently throughout the recording, the entire interview may be excluded.”

Multiple perspectives

Because interview subjects were generally recruited through two partners (the Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture and the Historic Resources Committee at the AIA Houston Chapter), most of the subjects in Building Houston worked in the same few firms or as architecture professors. They were all worthy of inclusion, but the collection failed to pull in other perspectives and experiences. The staff had to consciously seek out a more diverse field of subjects. A good strategy for developing a varied and inclusive collection is to create categories and then seek out good candidates for each category on an annual (or semiannual) schedule. Categories should include people from different eras, different sized firms, and different professions. Organizers should ensure that interview subjects represent all races, classes, and genders. Categories can also include people who use the designed spaces. A facility manager, for example, can provide information about how a structure is used, whether it is functional, or how a structure has been adjusted. A curator can speak about how they mount and reveal exhibits in a museum. Community leaders can talk about changes to their neighborhoods. Set designers can provide information about the technical aspects of a theater. These perspectives are very beneficial in helping students understand and appreciate the architecture they research.

Catherine Essinger has been the art architecture, and design librarian and the Jenkins Library director for 15 years. She is a past President of the Association of Architecture School Librarians and past Executive Board member of the Art Libraries of North America. She has published articles in Bright Lights Film Journal, Collaborative Librarianship, and Texas Library Journal. Her forthcoming book, The Sudden Selector’s Guide to Art Resources, is being published by the Association for Library Collections & Technical Services.

Questions

Michelle Sturges

Membership Manager

202-785-2324

msturges@acsa-arch.org

Study Architecture

Study Architecture  ProPEL

ProPEL