BACKGROUND AND GRAPHIC ANALYSIS

Sponsored by the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA), the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), and the Iowa State University, College of Design

Project Leader: Nadia M. Anderson, Assistant Professor, Iowa State University

April 20-22, 2011 | Host School: Iowa State University

Flood Extents & Floodplains

Affected Housing Types

Affected Parcels

In June 2008, the city of Cedar Rapids, Iowa was devastated by a flood event that affected much of the eastern part of Iowa. More than 14 per cent of the city was impacted by the floodwaters, 10,000 residents were displaced, and 5900 residential properties were flooded. Cost impacts included $376 million in damage to homes and a total of $1.3 billion total city costs including clean up, repairs to city buildings and infrastructure, and future flood management. Impacts were greatest in areas with higher than average socially vulnerable populations including minorities, the elderly, the disabled, female-headed households, and the low income.1

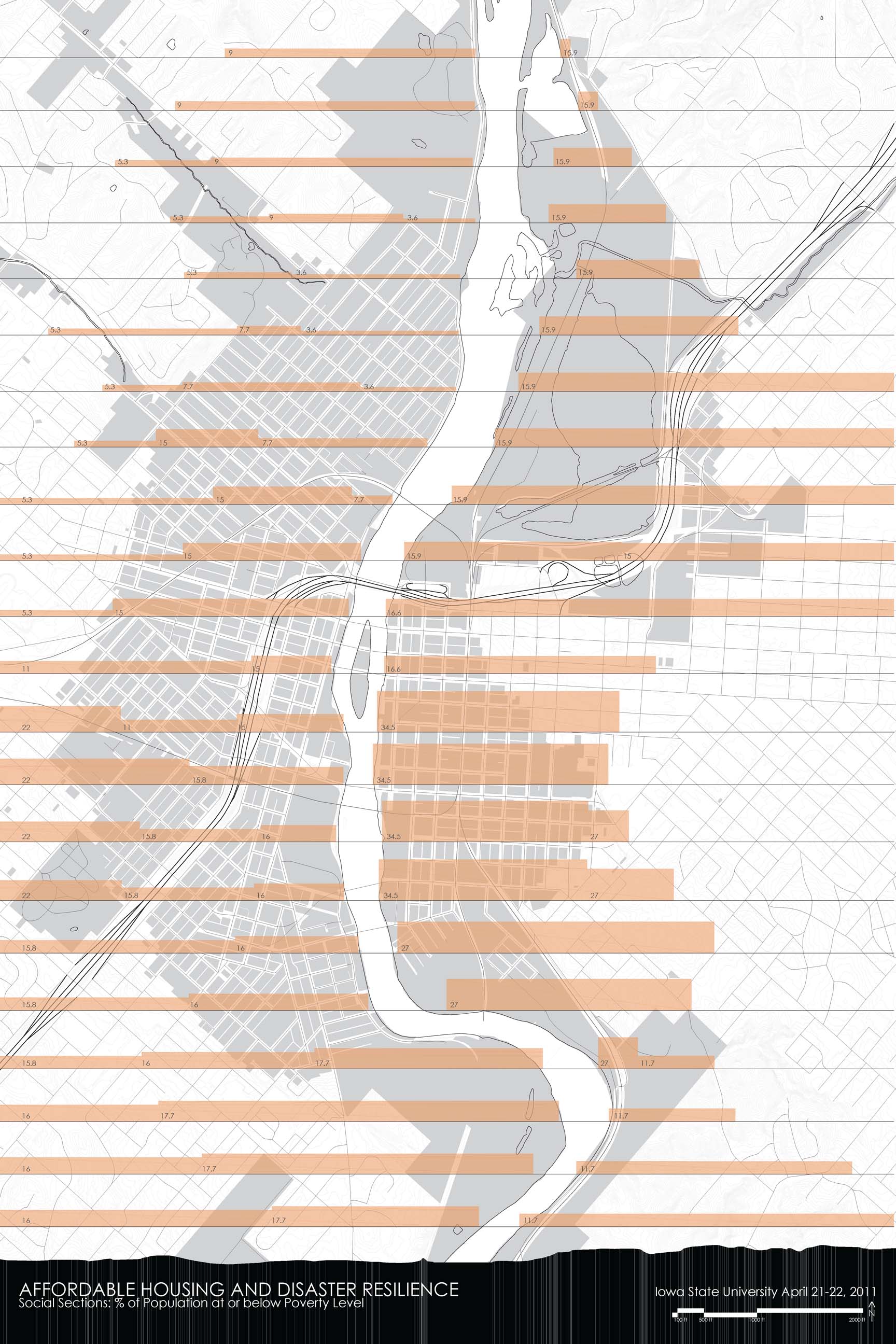

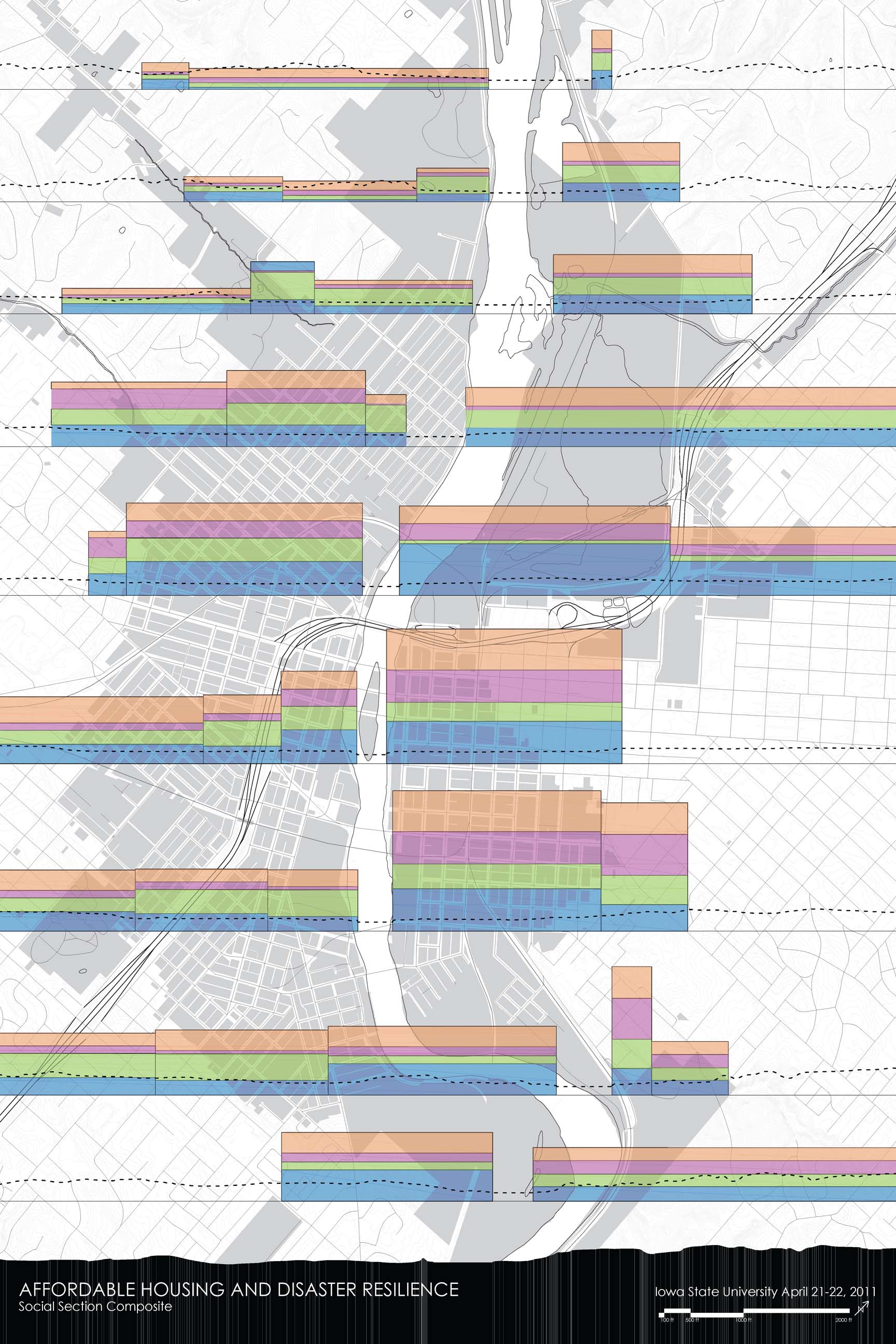

The “Affordable Housing and Disaster Resilience” project examines how the physical, environmental context of the city of Cedar Rapids has created social topographies that in turn create vulnerability and low resilience in the city’s most at-risk neighborhoods. Flood impacts demonstrate that the city’s physical configuration relative to the Cedar River and its floodplain creates inequitable social conditions that were exacerbated by the flood, resulting in greater hardship for those populations least able to deal with it. To demonstrate this, a series of graphic studies articulating the relationship between physical and social topographies in Cedar Rapids was presented at the symposium to frame discussion around the need to design for flood resilience in concert with existing environmental and social conditions.

% of Population at or below Poverty

% of Minority Population

% of Population at or above 65 Years Old

% of Rental Housing Units

Composite Social Topography

Post-Flood Planning

Since 2008, the City of Cedar Rapids has conducted a comprehensive planning and re-building process that has included design and engineering consultants (team led by Sasaki), the Army Corp of Engineers, FEMA, a range of state agencies, and most importantly the citizens of Cedar Rapids. Goals resulting from this process include:

- Rebuild high quality and affordable workforce housing and neighborhoods.

- Improve flood protection to better protect homes and businesses.

- Restore full business vitality.

- Preserve our arts and cultural assets.

- Maintain our historic heritage.

- Assure that we can retain and attract the next generation workforce.

- Help our community become more sustainable.2

The intent and desire of the community is clearly to coexist with the river system in spite of the risks that it creates for future flood events. Given the position of Cedar Rapids at the base of the Cedar River watershed, the on-going draining of agricultural land upstream, the on-going increase in impervious surfaces upstream, and the increased likelihood of flood events resulting from early snow melt and increased rain due to global climate change, a flood management strategy is needed that allows human beings to coexist with the dynamic river system if at all possible.3The proposed flood management strategy, as articulated in the Cedar Rapids Framework Plan, is primarily a structural one that relies on floodwalls and levies to protect surrounding business and residential areas from floodwaters. Significant areas, particularly on the west side of the river, have been designated as Greenway and Construction areas with properties eligible for various buy-out programs. The Army Corps of Engineers, in evaluating various proposed flood management strategies, determined that, according to their federally-mandated cost-benefit analysis, construction of the proposed system is only feasible on the east side of the river.4 A recent vote defeated a proposed local option sales tax through the city’s Growth Reinvestment Initiative to fund the rest of the flood protection plan; a re-vote is expected in November.

Cultural Context and Environmental Justice

Originally settled in the 1840s, Cedar Rapids was established as part of the westward migration of European-heritage settlers that transformed the Iowa landscape from tall grass prairie into a highly ordered, engineered and measured landscape. The Jeffersonian survey grid that creates the state’s political divisions and infrastructure reveals this transformation through its stark contrast to the regional watershed and other topographic features. Culturally, “nature” was a barrier to overcome or a resource to exploit, as with the natural falls occurring in the Cedar River at the site of the city’s founding and source of its initial industrial development. This attitude was coupled with a pastoral ideal of nature as a passive backdrop, as manifested in nineteenth and earlier twentieth centuries City Beautiful planning strategies. This cultural context frames current approaches to flood management that focus on fixed control of an inherently dynamic system.

These two attitudes toward nature also impacted the social configuration of the city, with more desirable properties and parks located on the higher hills around the river while industry, railyards, and accompanying worker housing were located in the lower areas adjacent to the river and vulnerable to flooding. Vibrant ethnic communities developed in these low-lying areas and the post-2008 flood desire to maintain the social integrity and cultural value of these areas is very strong.

Unfortunately, because of problems with the buy-out programs, most post-flood affordable replacement housing has been built outside of the flood-affected areas, although new building phases are now targeting these neighborhoods. New housing has also primarily been acquired by young people with small households, data that does not match the demographics of those most affected by the flood. Affordable rental housing is still greatly needed, as is income generating housing that can replace properties such as duplexes that were owned outright and provided owners with a primary source of income through the rental unit.

Proposal

In addition to flood protection, the proposed plan for the river also includes parks and recreation areas as community amenities. These areas continue, however, to follow the dualistic separation of human beings and nature present since the city’s founding. Greenways and parks run parallel to the river, for example, but never penetrate into the surrounding neighborhoods, creating a clear distinction between river and city, nature and people.

Instead of maintaining this division, perhaps it is possible; particularly on the west side of the Cedar River, to consider other, more integrated relationships between the river and the city. These strategies could rely on less structural measures for flood control while also providing community assets throughout neighborhoods rather than just at their edges. They could also enable houses to engage the street rather than lifting day-to-day life above the sidewalk in anticipation of flood events and could provide affordable housing solutions through alley rental properties, varying densities, and multi-household block strategies. All of these combine to create not only affordable but also sustainable and resilient neighborhoods.

The analysis work prepared as part of this research will be presented as a starting point for discussion about the potential for new approaches to flood management, affordable housing, and neighborhood design in the City of Cedar Rapids. The hope is that this will generate new collaborations and conversations that can lead to a broader consideration of the relationship between the city and the river and generate models for other communities attempting to become sustainable and disaster resilient rather than simply disaster resistant.

1 City of Cedar Rapids, “Other Social Effects Report: City of Cedar Rapids, Iowa – Flood of 2008,” June 7, 2010, 26-27, 51-53.

2 Sasaki Associates Inc., City of Cedar Rapids Framework Plan for Reinvestment and Revitalization, December, 2008, 3.

3 Other Social Effects, 46-49. See also multiple articles in Cornelia F. Mutel, ed., A Watershed Year: Anatomy of the Iowa Floods of 2008 (Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press, 2010).

4 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Rock Island District, Cedar River, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Flood Risk Management Project: Feasibility Study Report with Integrated Environmental Assessment, Final, October, 2010, 275-278.

Kendall Nicholson

Director of Research + Information

202-785-2324

knicholson@acsa-arch.org

Study Architecture

Study Architecture  ProPEL

ProPEL